“Senseless violence is a prerogative of youth, which has much energy but little talent for the constructive.”

― Anthony Burgess, A Clockwork Orange

From Sam Peckinpah to Stanley Kubrick, Quentin Tarantino and Oliver Stone, audiences’ thirst for ultraviolent content is palpable. Cinemagoers flock to theatres in search of cheap violent thrills. While these filmmakers’ works are unequivocally intoxicating, have we considered the social collateral of these bloodied visual feasts? Did the original creator of stylised violence, Sam Peckinpah, anticipate the longitudinal effects of his visual antics? Sleuth Hound takes a deep-dive into ultraviolent cinema and the legacy of Sam Peckinpah from gun-toting cowboys to celebrity serial killers.

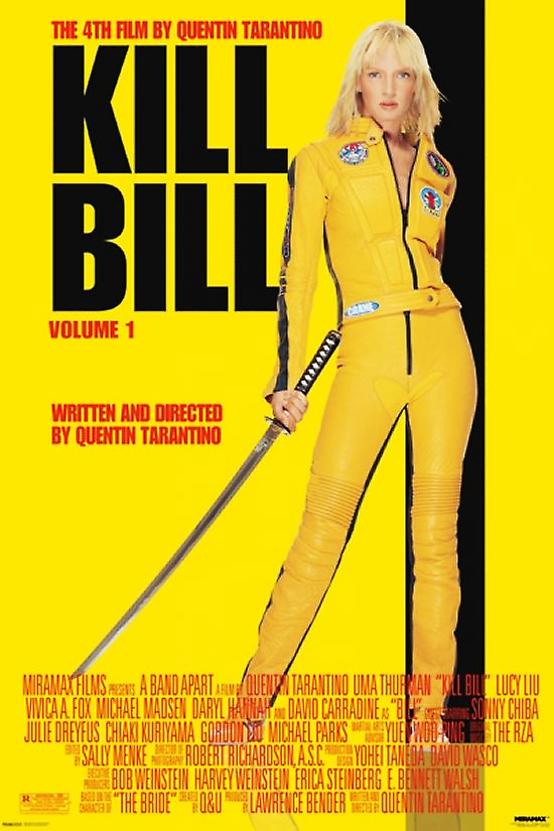

When Sam Peckinpah’s captivating film, The Wild Bunch, was first released in 1969, many viewers were both shocked and reviled at its ultraviolent content. Although highly controversial at the time, it has since achieved landmark status for its role in spearheading the development of aestheticized violence. The techniques developed by Peckinpah fashioned a new generation of filmmaking and have influenced contemporary directors including Quentin Tarantino and Oliver Stone. This article will consider the emergence of stylized representations of violence through the works of Peckinpah looking mainly at Straw Dogs (1971) and The Wild Bunch. Sleuth Hound will then investigate the ways in which he inspired postmodern texts like Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill Volume 1 (2003) and Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers (1994). Arguably, these films borrow explicitly from Peckinpah stylistically, however, they tend to privilege aesthetically choreographed imagery without considering any of the underlying ethical and social implications of violence.

Sam Peckinpah, Source: Google

The Wild Bunch

At the time The Wild Bunch was directed, the American public had largely become “inured” to violence. People had been regularly inundated with images of the Vietnam War televised alongside commercials, largely desensitizing them to its horror. Peckinpah was also critical of realist representations of violence which he felt had a “narcotizing [sic]” effect on audiences.

Peckinpah’s intention was to rouse people from their apathy by heightening and stylizing depictions of bloodshed. In an interview, he stresses that while his films are saturated with brutality they are actually “anti-violence,” and he hoped viewers would be “dismayed” and “sickened” by their content. For this reason, The Wild Bunch is a film with a clear moral agenda functioning as a metaphor for the “corrupt” and “ruthless” economic forces underscoring American modernization.

The narrative’s central trajectory follows a group of outlaws led by the aging Pike Bishop (William Holden) who engage in an ultimately ill-fated deal with Mexican warlord Mapache (Emilio Fernandez) to steal a shipment of weaponry from the American Army. In May 1969, a 190-minute version of the film was first shown at a theatre in Kansas City. More than 30 people walked out of the screening and the violence made several more physically ill. This prompted Peckinpah to review some of the film’s content with him stating in an interview, “If I’m so bloody that I drive people out of the theatre … then I’ve failed.” The final release was 145 minutes long and the film soon became the “… most talked about, commented upon… film of the year.” The movie was so profound and it generated such a stir because of its development of a number of visual stylistics which would radically transform cinematic portrayals of violence.

Peckinpah’s aestheticization of violence is characterised by the development of a number of stylistic montages. The three most significant montages included: one intercutting slow-motion and normal paced segments, another superimposing multiple clips, each set to different times and a montage where the viewer is encouraged to perceive social truths. A primary example of the slow-motion montage appears amid the chaos of the opening massacre in The Wild Bunch through a striking and poignant slow-motion shot of a wounded man as he falls from his horse. Stephen Prince describes the instance as capturing “… that moment when death or grievous wounding robs or threatens to rob the body of its spirit…”

An illustration of a more complex montage occurs in Straw Dogs through the first brutal rape of Amy (Susan George). The scene combines slow-motion close-ups of Amy’s horrified face with frenzied flashbacks of her relationship to David (Dustin Hoffman), as she comes to associate him with her attacker. This scene encourages the audience to identify with Amy’s suffering, but it also shows that violence is a pervasive human quality (through the association of Charlie with David), a point which becomes clearer as the narrative progresses. Moreover, it is precisely these stylistic montages coupled with a concern for representing the detrimental results of violence which proliferate many of Peckinpah’s most influential films.

Kill Bill: Cheap Thrill?

Peckinpah’s aesthetic techniques have inspired the films of contemporary director Quentin Tarantino. In the examples provided later on, Tarantino’s stylistic debt to Peckinpah is unquestionable but his approach is specifically postmodern. Glynn White describes his particular style as Tarantino-esque, a term which has become a “… by-word for both pop-cultural reference and postmodern cinema.” The postmodern aesthetic is typified by the dissolution of grand-narratives, the emergence of self-reflexivity, the blurring of generic and cultural boundaries, and a pre-occupation with the image (often at the expense of ethics). Arguably, it is precisely this disregard for ethics that distinguishes Tarantino from his morally-conscious forerunner. In fact, in an interview Tarantino states that he finds violence “funny” and “outrageous,” and he does not take it “very seriously.”

This outlook is clearly evident in Pulp Fiction (1994) when a hit-man (John Travolta) apathetically shoots a passenger, a moment emphasized cinematographically by the positioning of the camera behind the head. This is another point of deviation as Peckinpah generally avoided embellishing particularly carnal and bloodied moments in his films. This article focuses primarily however on Kill Bill, which is premised on the Bride’s (Uma Thurman) “roaring rampage of revenge” after the Deadly Viper Assassination Squad hijack her small-town wedding. This is a film which reveals both Tarantino’s stylistic debt to Peckinpah but also his departure from the moral concerns of his predecessor.

The “Crazy 88” scene is a clearly postmodern construction and it offers one of the most astonishing and spectacularly aestheticized moments in Kill Bill. The “Crazy 88” led by the immaculately dressed O-Ren Ishii (Lucy Lui) are introduced as black-suited, masked performers as they prepare to participate in a hyper-choreographed dance of death. O-Ren Ishii initially offers up a number of the weaker “Crazy 88” members whom the Bride effortlessly butchers. The first real challenge comes with Gogo Yubari (Chiaki Kuriyama), O-Ren Ishii’s 17-year-old chain-and-ball wielding bodyguard. The filming of this contest explicitly cites Peckinpah by interweaving real-time and slow-motion shots; Gogo waving around her chain-and-ball in real-time followed by the Bride’s slow-motion back-flip. Other explicitly postmodern moments in the scene include the black and white sequence and the spectacularly choreographed segment set against a blue wall in which the “performers” appear as black shadows dancing on a wall.

The Bride then faces Johnny Mo (Chia Hui) one of the more powerful “Crazy 88” members but she eventually disables him by severing his leg. It seems almost as though the Bride is passing through levels or stages in a game as she prepares to face her ultimate opponent, O-Ren Ishii. This match-up occurs outside the House of Blue Leaves against the beautiful and starkly white snow (a stage which emphasises the violence and bloodshed to follow). This breath-taking fight culminates in the dramatic scalping of O-Ren Ishii, marked by the slow-motion shot of her scalp flying through the air. The startling mis-en-scene of the “Crazy 88” dance of death functions as an intense and complex illustration of Tarantino’s ultra-violent style.

Vivienne Sobchack criticises violent postmodern films for presenting the slaughter of bodies in a detached, emotionless and “Fordist” production-line manner. In the above scene, the Bride butchers countless people with relative ease, underscored by a number of high-shots over the scattered corpses. In his text Savage Cinema, Stephen Prince also argues that Tarantino’s films function as a “pastiche” of pop-cultural iconography in which violence is perpetrated against movie characters instead of real human beings.

As alluded to previously, the “Crazy 88” are arguably not represented as “real” people rather they are masked performers without individual identities for the most part (excepting Gogo Yubari and Johnny Mo). Similarly, O-Ren Ishii becomes a larger-than-life caricature and in fact, in an earlier sequence she is explicitly depicted as a Japanese anime character. See below:

This in effect blurs the boundary between what Baudrillard describes as the “real” and the “hyper-real” (something which will be discussed further in relation to Natural Born Killers). Moreover, this potentially alienates audiences emotionally as they are encouraged to become immersed in a visually exciting spectacle without considering any of the underlying human costs and consequences of acts of violence.

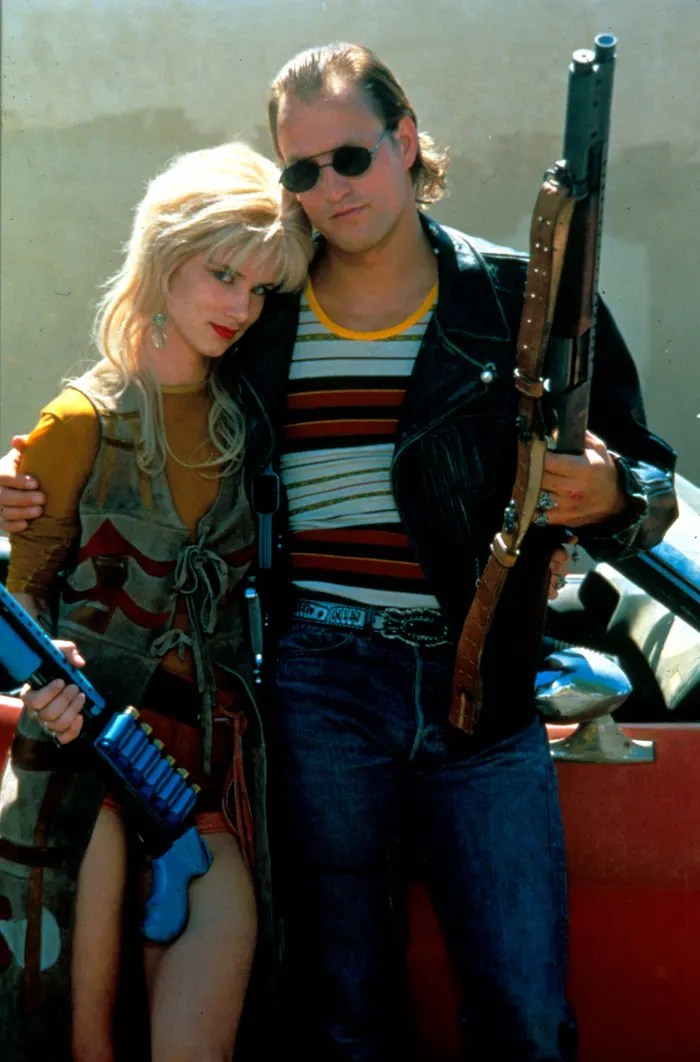

Natural Born Killers

As with Tarantino, Oliver Stone’s works are also stylistically influenced by Peckinpah, but his films tend to offer a more ambivalent approach to violence. In his earlier works such as Salvador (1986) and Platoon (1986), Stone more successfully engages the painful and horrific results of brutality. In Salvador, for example, the shocking manner in which the rape and murder of catholic women is filmed functions as a reminder of the horror and destruction generated by such acts. Natural Born Killers centers on the lives of Mickey (Woody Harrelson) and Mallory (Juliette Lewis) an “outlaw couple” whose “romantic devotion” to one another has drawn comparisons with Bonnie and Clyde.

This is a film which clearly borrows from Peckinpah in its aesthetics: consider the extended prison fight scene which intertwines slow-motion with real-time (the slow-motion shots of prisoners running away amid the chaotic brawl). Through the film, Stone aimed to highlight the negative impacts of American culture’s media obsession (which has led to the idolisation of serial killers such as Charles Manson, O.J Simpson and Ted Bundy) but the film inadvertently becomes “… the very thing it wished to expose…”

This is partly the result of Stone’s infectious admiration for Mickey and Mallory and also because they are positioned as the film’s most sympathetic characters when distinguished from the “… gallery of grotesque and depraved characters who surround them.” The kinds of deplorable characters I am referring to here are Detective Jack Scagnetti (Tom Sizemore) (who strangles a prostitute to death and tries to rape Mallory) and journalist Wayne Gale (Robert Downey Jr.) who we discover has been cheating on his wife. Moreover, despite Stone’s initial intentions the film becomes a glamorous, funky and cool tribute to violence rather than a sustained condemnation of it.

Natural Born Killers’ postmodern aesthetic is developed by the amalgamation of different media together. For example, the film intertwines animated sequences, clips from “American Maniac” (a take-off of “America’s Most Wanted”) and interviews with adoring fans with one professing, “… if I were a mass murderer, I’d be Mickey and Mallory.” The postmodern stylistic is further developed by the depiction of Mallory’s life story in the television show “I love Mallory.” Her celebrity persona becomes indistinguishable from the so-called “real” Mallory seen in other parts of the film. However, the most explicitly postmodern scene of the film is arguably the “Log Cabin Lodge” sequence.

In this scene, the frantic camera goes back and forth between a television set (playing animal documentaries, clips from The Wild Bunch, footage of the chainsaw killing in Scarface (1983)), the window which also becomes a screen and the activities of Mickey and Mallory. During this visual frenzy, the pair begin to have sex while Mickey watches their latest victim, a woman who is tied up and barely clothed which causes a disconcerted Mallory to ask, “Why are you looking at her?” This moment explicitly references another kind of pop-cultural phenomena, the emergence of derogatory “Adult Films” which sexualise and degrade women. The above clearly postmodern moments in Natural Born Killers have important ramifications for the film’s overall message.

These selected segments demonstrate the kind of complex postmodern aesthetic at play in Natural Born Killers, one which problematises Stone’s depictions of violence. In drawing upon various pop-cultural iconography, the film blurs the binary between the “referentially fictional” and the “referentially real” (much like what happens in Kill Bill). This is clearly seen in the “Log Cabin Lodge” scene through the various dizzying camera shifts between the television, the screen on the window and the activities of Mickey and Mallory. As with Kill Bill, the potential outcome of this is that spectators fail to respond emotionally to the violence or the human suffering it can generate.

The intermixing of different media in such an outrageous way also serves to give the brutality an almost comical quality and certainly the audience is not encouraged to take the rape and strangling death of a prostitute too seriously, underscored by the fact Scagnetti is never formally punished. This is a world of people desensitised to human suffering, a world where people are encouraged to simply “switch-off” to the negatives of violence (just as easily as the apathetic gum-chewing barwoman turning the television off in film’s opening sequence). Arguably the only two characters that spectators are encouraged to identify with are the loved-up “murderers” rather than their victims.

This non-chalant disposition to violence is clear during the killing of Wayne Gale in which both Mickey and Mallory are laughing and audiences are similarly encouraged to find the moment comical. We are certainly not invited to sympathise with weedy fame and money-hungry Wayne Gale who cheated on his wife. He deserves it. Ultimately, as a result Stone sacrifices ethics for the entertaining image in his morally-deficit tribute to violence. The irony of it all is that this is precisely the “anti-thesis” of the kind of morally-conscious portrayal of violence that Peckinpah wanted to achieve in stylising violence.

Ultraviolent Films: Style over Sustance?

This article first considered the emergence of stylistic representations of violence through The Wild Bunch and Straw Dogs, films successful in locating violence as a destructive social force. Subsequently, Sleuth Hound then argued that the works of contemporary filmmakers Oliver Stone and Quentin Tarantino have been stylistically influenced by Peckinpah, looking in particular at Kill Bill and Natural Born Killers. However, these films are specifically postmodern, meaning that their central focus is the aesthetically choreographed image above any ethical concerns. The result is two highly choreographed, seductive, hypnotising but morally-vacuous films. It is a clear case of style over substance.

Leave a comment