The concept of “madness” has long fascinated famous writers, lyricists and poets. It was Sylvia Plath who wrote “Mad Girl’s Love Song,” an ode to every woman who has ever found herself in a situation of unrequited love. Of course, a more visceral representation of a person’s descent into “molten madness” can be seen in Lewis Caroll’s seminal text Alice in Wonderland wherein the titular character, Alice, embarks on a hapless pursuit of a White Rabbit and she ends up descending down a Rabbit Hole.

Alice, naturally beguiled and confused at having fallen down the proverbial Rabbit Hole, finds herself in Wonderland, a world full of colorful characters including talking Cheshire cats, mad hatters and hookah smoking caterpillars. Alice’s fantastical journey is often used as an analogy for people society deems unmoored from reality – that is, those who are experiencing cognitive dissonance or some kind of disconnect from the “real” or what French sociologist Baurillard might characterize as the chasm between the ‘real’ and the ‘hyper-real.’

In some senses the invocation of the image of woman falling down a Rabbit Hole to denote some kind of mental fallibility may be seen as disparaging to sufferers of mental anguish. However, to be clear, nothing is this article is designed to denigrate or cast aspersions on vulnerable members of the community with mental health concerns. Rather, this piece aspires to antagonize the notion that the trope of “madness” is used as a weapon in abusive men’s arsenal to discredit their victims and juxtapose this against a consideration of the collateral of such a devastatingly nefarious tactic. This is the first in a series of articles which delve into the diabolical patterns of behavior that abusive men partake of in order accountability for their actions.

Alice Tumbling Down the Rabbit Hole, Source: Google

Madness is a trope often associated with women. Freud, the controversial Father of Psychoanalysis, whose research methods left a lot to be desired, would often diagnose women as “hysterical.” Throughout its history, hysteria was a sex-selective disorder, and Freud contended that its antecedents lay in women’s inability to reconcile the loss of their metaphorical phallus. It was this alleged sorrow spurred from the lack of a penis which was said to catalyze women into a state of being ‘over-emotional’ and ‘unhinged.’ In fact, it is worth noting that the word hysteria has its etymological roots in the Greek word for ‘uterus.’ Thus, it appears that madness and all the negative stereotypes associated therein have always been associated with the feminine. It is with a certain turgid chagrin that I note that we have been paying the price Freud’s misogynistic and questionable diagnostic methods ever since.

Problematically, throughout history (and even today), women who express discontent (or any kind of emotion) are quickly labelled “mad,” “crazy” or my personal favorite, “psycho.” This is particularly diabolical when abusive men use these terms to denounce the experiences of their female victims, especially in circumstances where they have taunted her so significantly and traumatized her to the point that they can conveniently characterize any of arguably natural reactions to abuse as symptomatic of her inherent “madness.” This might be followed by the quick quip, “see I told you she was mad,” as if this is an affirmation that she’s in fact the problem and he’s the innocent victim of a mad woman. This of course feeds the narrative that any allegations she might raise now or in future about his unconscionable behavior have no credibility because “she’s madder than a March Hare.”

Other literary representations of “mad women” appear in canonical texts including Charlotte Bronte’s famous Jane Eyre. In this text Bertha Mason is confined to the attic and denounced as ‘mad,’ ‘violent’ and ‘crazy.’ While on the one hand some of her behaviors may be characterized as evidence of the aforesaid, her behavior becomes more understandable when understood through the lens of the repressive social infrastructure in which she finds herself. Namely, Bertha was a victim of the repressive constraints of Victorian society, and her anger was perhaps quite rightly fueled by the repressive social regime of the time. We must remember this was a time when women’s voices were marginalized and therefore her anger at her forced imprisonment and the patronizing treatment, she is subjected to is more than justifiable. In fact, we should look with scathing contempt at the men who had the audacity and nerve to keep her in these untenable conditions.

One of the original “mad women” of cinema was Ingrid Bergman’s poignant and compelling portrayal of Paula Alquist in the 1944 psychological thriller Gaslight. The terms ‘gaslighting’ is said to derive from this film which focuses on a man who systematically drives his wife “crazy,” making her question her reality including by causing her to believe she has lost some of her valuable possessions (notably a broach). By making her believe she is going crazy or “mad” her antagonizer is able to control her more easily and discredit her lived experience. Diabolically he also co-opts other characters into his abuse including the servant played by Angela Lansbury – all done with the malevolent design of making her believe she has descended into madness.

One of the film’s most powerful scenes is when Paula Alquist regains her power in the end. She finally figures out his macabre agenda and she throws the mad woman trope in his face as he, rather astoundingly and in a rather ironic twist of fate, begs his victim for help. She decides, rather sagaciously, that she is not going to help her tormentor and that she will allow him to fester in his own cesspool of vileness. The scene can be viewed here:

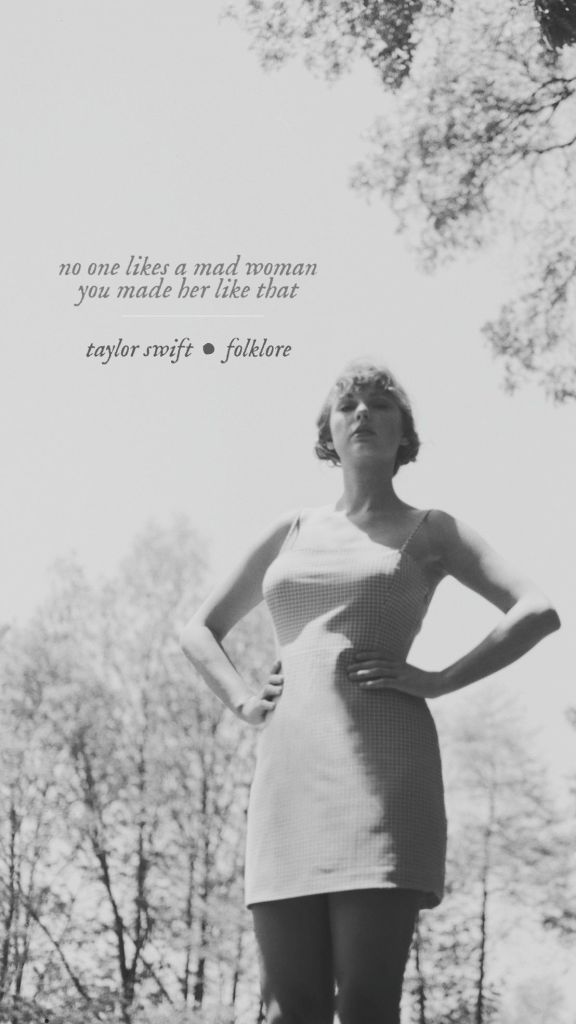

Recently, Taylor Swift took aim at the “mad woman” trope in her delightfully clever song of the same title. Many believe the song is about Swift’s long-standing feud with Scooter Braun who appropriated the rights to her songs, a move which infuriated her and left her feeling voiceless. However, the song is also about men’s violent behavior to women in particular through gaslighting, breadcrumbing, love-bombing and ultimately, the abuser’s endeavors to paint his victim as the person with the problem.

The song is so pivotal in explaining the dynamics of abuse that it is worth excerpting some of the lyrics.

Every time you call me crazy

Taylor Swift

I get more crazy

What about that?

And when you say I seem angry

I get more angry

And there’s nothin’ like a mad woman

What a shame she went mad

No one likes a mad woman

You made her like that

And you’ll poke that bear ’til her claws come out

And you find something to wrap your noose around

And there’s nothin’ like a mad woman

Dr Jennifer Freyd who established the Center for Institutional Courage. Through her seminal research into both sexual abuse and institutional betrayal she coined the term DARVO. DARVO is an acronym which stands for (D) deny (A) attack (R) reverse (V) Victim and (O) offender. In essence, perpetrators use this tactic when confronted with allegations of wrongdoing to thwart their accuser’s endeavors to hold them to account. The function of DARVO is to “muddy the waters” and beguile the system with endless character attacks about the victim and ultimately to place themselves as the truly aggrieved party in order to drum up sympathy and divert attention from their own unconscionable behavior. While a more in-depth analysis of DARVO and its mechanisms will feature in subsequent articles, it is worth a brief mention merely to elucidate the mechanisms deployed by abusive men.

Mad or Abused?

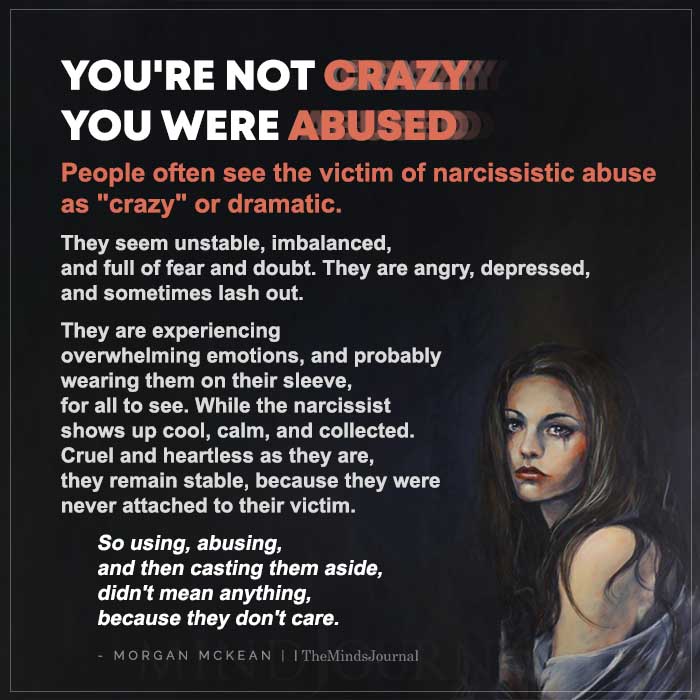

Often the women men attempt to portray as “mad” have simply been abused. It is normal for women who have been abused to behave in erratic and emotional ways. Such reactions, when viewed through a trauma-informed lens, ought to be viewed as normal in the context of abusive relationships.

Failure to understand the complex nuances of domestic abuse can have deleterious and profound consequences for abused women. For example, in the recent Gabby Petito case, police misidentified that Gabby Petito was the real victim because when called to the scene of a domestic incident she was erratic, while her abuser appeared the cool, calm and collected narcissist. While a full appraisal of the Gabby Petito case will be rendered at a later date, it illustrates the problems that arise when police and other law enforcement officials are not trauma-informed.

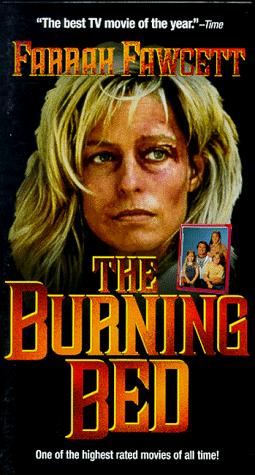

Beds Are Still Burning

The distinction between a genuinely “mad” woman and an abused woman could be seen very viscerally in the landmark case of Francine Hughes. In March 1977, Francine killed her husband, Mickey Hughes, by pouring gasoline around his bed and setting him alight. She then got into her Ford Granada, drove to the county jail and declared rather hysterically, “I did it!” At first glance, to seasoned investigators, this was just another black and white case of spousal homicide and they arrested and indicted her for murder. At trial, Francine adduced a wealth of evidence that showed that she had suffered 14 years of horrific domestic violence at the hands of the deceased. Her lawyers argued that she had simply ‘snapped’ on the night of his death. The jury, composed of ten women and two men, delivered a stunning and unprecedented verdict of not guilty by reason of temporary insanity. While this case was a watershed decision for the way that it highlighted questions about the legal treatment of battered women who kill, it most certainly did not resolve these questions and the debate rages on in courts across the globe. Sleuth Hound recognises that while the verdict, prima facie, in the case may seem auspicious for battered women’s cases, in fact, portraying battered women as disordered and crazy is not beneficial (a topic which will be expounded upon in further detail at a later date).

Whatever way you look at it, beds are still burning and women’s calls for help are still being left unanswered. Embodying a greater understanding of abused women’s plights and repudiating mythologies around “mad” women may be a first start in helping to garner an appreciation both of men’s gaslighting tactics and also of the complex nuances of battered women’s narratives of suffering and pain.

Leave a comment